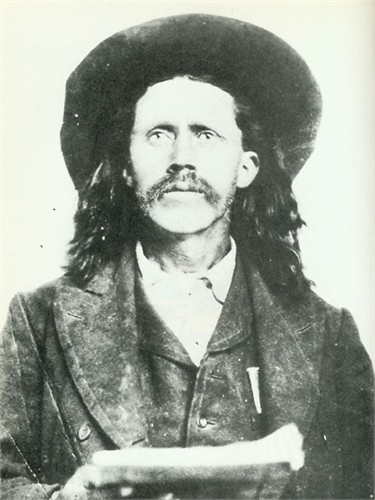

Saint Jean de Brébeuf (March 25, 1593 – March 16, 1649) was a French Jesuit missionary who traveled to New France (or Canada) in 1625. There he worked primarily with the Huron for the rest of his life, except for a short time back in France in 1629-1630. He learned their language and culture.

In 1649 Brébeuf and several other missionaries were captured when an Iroquois raid took over a Huron village. Together with Huron captives, the missionaries were ritually tortured and eight were killed, martyred on March 16, 1649. Brébeuf was beatified in 1925 and canonized as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church in 1930.

Biography

Early years

Brébeuf was born 25 March 1593 in Condé-sur-Vire, Normandy, France. He became the uncle of poet Georges de Brébeuf. He joined the Society of Jesus in 1617 at the age of 24, spending the next two years under the direction of Lancelot Marin. Between 1619 and 1621, he was a teacher at the college of Rouen. He was nearly expelled from the Society because he contracted tuberculosis in 1620—an illness which prevented both studying and teaching for the traditional periods.

His record as a student was not particularly distinguished, but he was already beginning to show an aptitude for languages. Later in New France, he would become a language teacher to missionaries and French traders.(Leahey 106). Brébeuf was ordained as a priest at Pontoise in 1622.

Missionary

After three years as Steward at the College of Rouen, Brébeuf was chosen by the Provincial of France, Father Pierre Coton, to embark on the missions to New France. In June 1625 Brébeuf arrived in Quebec with Fathers Charles Lalemant and Énemond Massé, together with the lay brothers Francois Charton and Gilbert Burel. For about five months Brébeuf lived with a tribe of Montagnais, and was later assigned in 1626 to the Huron with Father Anne Nouée. Brébeuf worked mostly with the Huron, an Iroquoian-language group, as a missionary in North America. Brébeuf briefly took up residence with the Bear Tribe at Toanché. In 1629 he was recalled to France when the post was retaken by the First Nations.

In Rouen Brébeuf served as a preacher and confessor, taking his final Jesuit vows in 1630. Between 1631 and 1633, Brébeuf worked at the College of Eu in northern France as a steward, minister and confessor. He returned to New France in 1633, where he spent the rest of his life.

Along with Antoine Daniel and Ambroise Davost, Brébeuf chose Ihonatiria (Saint-Joseph I) as the centre for missionary activity with the Hurons. At the time, the Huron suffered epidemics of newly introduced Eurasian diseases contracted from the Europeans. Their death rates were high, as they had no immunity to the diseases long endemic in Europe. They blamed the Europeans for the deaths, without understanding the causes.

Called ‘Echon’ by the Hurons, Brébeuf had an ambivalent relationship with the Natives. He was personally involved with teaching and caring for the Huron, and his conversations with Huron friends left him with a good knowledge of their culture and understanding of spirituality. He learned their language and taught it to other missionaries and colonists. Fellow Jesuits such as Rageuneau describe his ease and adaptability to the Huron way of life.

His efforts to develop a complete ethnographic understanding of the Huron has been described as ‘the longest and most ambitious piece of ethnographic description in all the Jesuit relations’. Brébeuf tried to find parallels between the Huron religion and Christianity, to facilitate conversion of the Huron to the European religion. Brébeuf’s also was known by the Huron for his apparent shamanistic skills, especially in rainmaking. Brébeuf considered Huron spiritual beliefs to be ‘foolish delusions’ and was determined to convert them to Christianity. The priest did not enjoy universal popularity with the Huron, as many believed he was a sorcerer. They were ultimately instrumental in his death.

His progress as a missionary was very slow, and only in 1635 did some Huron agree to be baptized as Christians. He claimed to have made 14 converts as of 1635, and by the next year, he claimed 86. Among his important descriptions of Huron ceremonies was his detailed account in 1636 of The Huron Feast of the Dead, a mass reburial of remains of loved ones after a community moved the location of its village. It was accompanied by elaborate ritual and gift-giving. In the 1940s, an archeological excavation was made at the site Brébeuf had described, confirming many of his observations.

In 1638, Brébeuf turned over direction of the mission at Saint-Joseph I to Jerome Lalemant; he moved on to become Superior at his newly founded Saint-Joseph II. In 1640, after an unsuccessful mission into Neutral Nation territory, Brébeuf broke his collarbone. He was sent to Quebec to recover, and worked there as a mission procurator. He taught the Huron, acting as confessor and advisor to Ursulines and religious Hospitallers. On Sundays and feast days, he preached to French colonists.

Brébeuf returned to Huron Country in 1644. There was unrest, and he was killed by the Natives in 1649.

Linguistic work

Jean de Brébeuf is distinguished for his commitment to learning the Huron language. The educational rigor of the Jesuit seminaries prepared missionaries to acquire native languages. As they learned the classical and romance languages, they must have had difficulty with the very different conventions of the New World indigenous languages. would make the process extremely difficult as native languages did not follow the same conventions His study of the language was also shaped by his religious training, as the existing theological ideas tried to reconcile knowledge of world languages with accounts in the bible of the tower of Babel. This influence can be seen in his discussion of language in his accounts collected in the Jesuit Relations.

Brébeuf had a remarkable facility with language, which was one of the reasons he was chosen for the Huron mission in 1626. Linguistic data suggests that people with a strong positive attitude towards the language community often learn the language much more easily.

Brébeuf worked tirelessly to become fluent in the language and to record his findings for the benefit of other missionaries. He built on the work of Recollet Priests, but significantly advanced the study, particularly in his representations of sounds. Brébeuf was widely acknowledged to have best mastered the Native oratory style, which used metaphor, circumlocution and repetition. Learning the language was still onerous, and he wrote to warn other missionaries of the difficulties.

To explain the low number of converts to possibly disappointed audiences, Brebeuf suggested this was due to the missionaries first having to master the Huron language. His commitment to this work demonstrates he understood that mutual intelligibility was vital for communicating complex and abstract religious ideas and imperative for the future of the Jesuit missions. Also, it was so difficult a task as to consume most of the Priest’s time. Brébeuf felt his primary goal at this time was to learn the language.

With increasing proficiency in Wyandot, Brébeuf became optimistic about communicating with the Huron and advancing his missionary goals. With a greater capacity to understand Huron religious belief and to communicate Christian fundamentals, he could secure converts to Christianity. He realized the people would not give up all their traditional beliefs., though not necessarily to the exclusion of the existing spiritual landscape.

Brébeuf discovered and reported the feature of compound words in Huron, which may have been his major linguistic contribution. This breakthrough had enormous consequences for further study, becoming the foundation for all subsequent Jesuit linguistic work.

With his singular language proficiency, Brébeuf pursued projects that would contribute to the spiritual mission of the Jesuits. He translated Ledesma’s catechism from French to Huron, which was the first printed text in that language. He also compiled a dictionary of Huron words, emphasizing translation of religious phrases, such as from prayers and the Bible.

Death

Brébeuf was killed at St. Ignace in Huronia on March 16, 1649. He had been taken captive with Gabriel Lalemant when the Iroquois destroyed the Huron mission village at Sainte-Louis. The Iroquois took the priests to the occupied village of Taenhatenteron, where they subjected the French men to ritual torture. The Iroquois finally killed them. Five Jesuits: Antoine Daniel, Lalement, Charles Garnier, Noel Charbanel, and Brébeuf, were killed in this conflict. The Jesuits considered their martyrdom proof that the mission was blessed by God and would be successful.

Throughout the torture, Brébeuf was reported to have been more concerned for the fate of the others and the captive Native converts than for himself. As part of the ritual, the Iroquois drank his blood, as they wanted to absorb Brébeuf’s courage in enduring the pain. The Iroquois mocked baptism by pouring boiling water over his head. They claimed that they were hurting him so that he would be happier in Heaven, as Jesuits preached that “the more one suffers on earth, the happier he is in Heaven”.

The Jesuits Christophe Regnault and Paul Ragueneau provided the two accounts of the deaths of Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalement. According to Regnault, the Jesuits learned of the tortures and deaths from Huron refugee witnesses, who had escaped from Saint-Marie. Regnault went to see the bodies to verify the accounts, and his superior Rageuneau’s account was based on him. The main accounts of Brébeuf’s death come from the Jesuit Relations. Jesuit accounts of his torture emphasize his stoic nature and acceptance, claiming that he suffered silently without complaining.

Martyrdom was a central component of the Jesuit missionary identity. Missionaries going to Canada expected to die in the name of God; they believed this was a chance to save converts and be saved. Martyrdom was associated with holiness. Both were associated with the expansion of Christendom throughout the world.

Relics, beatification and canonization

Father Brébeuf and Lalement were together buried in a Sainte Marie cemetery after their executions. However, Brébeuf’s relics, or what was left of his body, became important objects within the Catholic space of New France. On 21 March 1649, Jesuit inspectors found the bodies of Brébeuf and Lalement and buried them. Their exhumation coincided with the 1649 withdrawal of the Jesuits from New France, and the remaining body of Brébeuf was prepared by Christophe Regnault for transportation. Regnault boiled away any remaining flesh, scraped the bones then dried them in an oven, wrapped each relic in separate silk, deposited them in two small chests, and sent them to Québec.

Brébeuf’s family later donated his skull in a silver bust, and it was held by the Québec Hôtel-Dieu nuns and the Ursuline convent from 1650 until 1925, when the relics were moved to the Québec Seminary for his beatification. These relics provided physical access to the holy influence of the saint whom they are a part, and were to be called upon for their energy and connection.

In 1652 Paul Raguenau went through the Relations and pulled out material relating to the martyrs of New France and formalized them all in a document, to be used for the foundation of canonization proceedings, entitled “Memoires touchant la mort et les vertus (des Pères Jesuits)” or the Manuscript of 1652. The religious communities in New France were impacted by the Jesuits’ martyrdom, since they saw them as imitators of previous saints in the Catholic Church. In this sense, Brébeuf in particular, and others like him, connected Catholics of New France to their parishes because it reinforced the notion that “…Canada was a land of saints”.

Any candidacy for sainthood must provide evidence of miracles from the afterlife, and Brébeuf was no exception. His appearance is said to have appeared to Catherine de Saint-Augustine at the Québec Hôtel-Dieu while she was in a state of “mystical ecstasy,” and acted as her spiritual advisor. One story exists in which Catherine de Saint-Augustine ground up part of his bone and fed it in a drink to a heretical and mortally ill man. It is said that the man was not only cured of his disease. Continuing this trend, a possessed woman was exorcised using one of his ribs, again under the care of Catherine de Saint-Augustine in 1660-61; however, the exact circumstances of this event are disputed. Brébeuf’s relics even managed to be used by nuns who were treating wounded Huguenot soldiers, who “reported that his assistance [bone slivers put in soldiers’ drinks] helped rescue these patients from heresy”. His relics became important objects both for the nuns who often used them in a medical setting, but also to those who admired what he represented for the Catholic Church in New France.

Jean de Brébeuf was canonized by Pope Pius XI on 29 June 1930, and proclaimed one of the patron saints of Canada by Pope Pius XII on 16 October 1940. A contemporary newspaper account of the canonization declares: “Brébeuf, the ‘ajax of the mission’ stands out among them [others made saints with him] because of his giant frame, a man of noble birth, of vigorous passions tamed by religion” (New York Times, 19 June 1930), solidifying both the man and his defining drive.

Modern Times

It is said that the modern name of the Native North American sport of lacrosse was first coined by Brébeuf who thought that the sticks used in the game reminded him of a bishop’s crosier (crosse in French, and with the feminine definite article, la crosse).

He is buried in the Church of St. Joseph at the reconstructed Jesuit mission of Sainte-Marie among the Hurons across Highway 12 from the Martyrs’ Shrine Catholic Church near Midland, Ontario. A plaque near the grave of Jean de Brébeuf and Gabriel Lalemant was unearthed during excavations at Ste Marie in 1954. The letters read “P. Jean de Brébeuf /brusle par les Iroquois /le 17 de mars l’an/1649” (Father Jean de Brébeuf, burned by the Iroquois, 17 March 1649.

In September, 1984, Pope John Paul II prayed over Brébeuf’s skull before saying an outdoor Mass on the grounds of the Martyrs’ Shrine. Thousands of people came to hear him speak from a platform built especially for the day.

Many Jesuit schools are named after him, such as Collège Jean-de-Brébeuf in Montreal, Brébeuf College School in Toronto and Brebeuf Jesuit Preparatory School in Indianapolis, Indiana. St. John Brebeuf Regional Secondary School in Abbotsford, British Columbia, Canada and St. Jean de Brebeuf Catholic High School in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada are also named in his honour. There is a high school St-Jean de Brebeuf Catholic High School in Vaughan, Ontario, Canada. There is also Eglise St-Jean de Brebeuf in Sudbury, Ontario. There is also an elementary school in Brampton, Ontario, Canada named after him; called St. Jean Brebeuf Roman Catholic Elementary School as well as one in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada called St. John Brebeuf Catholic School which is part of the St. John Brebeuf Catholic Parish.

The parish municipality of Brébeuf, Quebec is named after him, as is rue de Brébeuf on the Plateau Mont-Royal in Montreal.