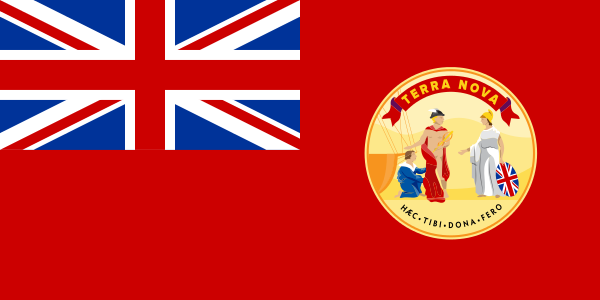

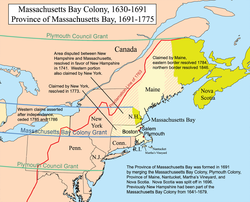

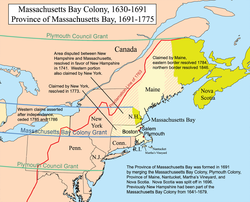

The Province of Massachusetts Bay was a crown colony in North America and one of the thirteen original states of the United States. It was chartered on October 7, 1691 by William and Mary, the joint monarchs of the kingdoms of England, Scotland and Ireland. The charter took effect on May 14, 1692 and included the Massachusetts Bay Colony, the Plymouth Colony, the Province of Maine, Martha’s Vineyard, Nantucket, Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. The modern Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the direct successor; Maine is an independent state, and Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are Canadian provinces.

The name Massachusetts comes from the Massachusett, an Algonquian tribe. The name has been translated as “at the great hill”, “at the place of large hills”, or “at the range of hills”, with reference to the Blue Hills, and in particular, Great Blue Hill.

Background

Colonial settlement of the shores of Massachusetts Bay began in 1620 with the founding of the Plymouth Colony. Other attempts at colonization took place throughout the 1620s, but expansion of English settlements only began on a large scale with the founding of the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1628 and the arrival of the first large group of Puritan settlers in 1630 Over the next ten years there was a major migration of Puritans to the area, leading to the founding of a number of new colonies in New England. By the 1680s the number of colonies had stabilized at five: in addition to Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth, Connecticut, Rhode Island and New Hampshire all bordered the area. Massachusetts Bay was the most populous and economically significant, housing a sizable merchant fleet.

The colonies at times struggled against the local Indian population, which had suffered a serious decline in population (most likely at the hands of infectious diseases brought over by European traders and fishermen) prior to the arrival of the first permanent settlers. In the 1630s the Pequot tribe was virtually destroyed, and King Philip’s War in the 1670s resulted in the expulsion, pacification, or killing of most of the Indians in southern New England. The latter war was also costly to the colonists of New England, putting a halt to expansion for several years.

Massachusetts and Plymouth were both somewhat politically independent from England in their early days, but this situation changed after the restoration of Charles II to the English throne in 1660. Charles sought closer oversight of the colonies, and to introduce and enforce economic control over their activities. The Navigation Acts passed in the 1660s were widely disliked in Massachusetts, where merchants often found themselves trapped and at odds with the rules. However, many colonial governments, Massachusetts principally among them, refused to enforce the acts themselves, and took matters one step further by obstructing the activities of the Crown agents themselves. The religiously conservative Puritan rulers of Massachusetts also refused to tolerate the Church of England, and yet at the same time were intolerant of other religious groups, banishing Baptists and executing Quakers who defied their banishment. These issues and others led to the revocation of the first Massachusetts Charter in 1684.

In 1686 Charles II’s successor, King James II, formed the Dominion of New England, which ultimately joined all of the British territories from Delaware Bay to Penobscot Bay into a single political unit. The Dominion’s governor, Sir Edmund Andros, was highly unpopular in the colonies, but was especially hated in Massachusetts, where he angered virtually everyone by enforcing of the Navigation Acts, vacating land titles, appropriating a Puritan meeting house as a site to host services for the Church of England, and his restriction of town meetings, among other sundry complaints. When James was deposed in the 1688 Glorious Revolution, Massachusetts political leaders conspired against Andros, arresting him and other English authorities in April 1689.This led to the collapse of the Dominion, as the other colonies then quickly reasserted their old forms of government.

The Plymouth colony had never had a royal charter, so its governance had always been on a somewhat precarious footing. Massachusetts, however, was placed into constitutional anarchy by the uprising. Although the colonial government was reestablished, it no longer had a valid charter, as a result of which some opponents of the old Puritan rule refused to pay taxes, and engaged in other forms of protest. Provincial agents traveled to London where Increase Mather, representing the old colony leaders, petitioned new rulers William and Mary to restore the old colonial charter. When King William learned that this might result in a return to the predominantly entrenched religious rule, he refused. Instead, the Lords of Trade decided to solve two problems at once by combining the two colonies. Accordingly on October 7, 1691, they issued a charter for the Province of Massachusetts Bay, and appointed Sir William Phips its governor.

Provincial charter

The new charter differed from the old one in several important ways: one of the principal changes, inaugurated over Mather’s objection, was to change the test requirements for attaining voting eligibility from religious to financial. Although the effect of this change has been subject to debate among historians, there is significant consensus that it greatly enlarged the number of men eligible to vote. The new rules required prospective voters to own £40 worth of property, or real estate that yielded at least £2 per year in rent, and has been estimated to have thus included three quarters of the then adult male population as eligible.

The second major change was that senior officials of the government, including governor, lieutenant governor, and judges, were appointed by the crown instead of being elected. The legislative assembly, or General Court, continued to be elected, however, and was responsible for choosing members of the Governor’s Council. The governor had veto power over laws passed by the General Court, as well as over appointments to the council. These rules differed in important ways from the royal charters enjoyed by other provinces. The most important were that the General Court now possessed the powers of appropriation, and that the council was locally chosen and not appointed by either the governor or the Crown. These significantly weakened the governor’s power, something that came to be of importance later in provincial history.

A third reason for the changes may have been to reduce the deadly influence of religious superstition in the colony, as evidenced by the Salem Witch Trials, which also occurred in 1692.

The province’s territory was also greatly expanded beyond that originally claimed by the predecessor Massachusetts and Plymouth colonies. In addition to their territories, which included present-day mainland Massachusetts, western Maine, and portions of all of the neighboring modern states, the territory was expanded to include Acadia or Nova Scotia (then encompassing modern Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and eastern Maine), as well as what was then known as Dukes County in the Province of New York, consisting of the islands of Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, and the Elizabeth Islands.

History

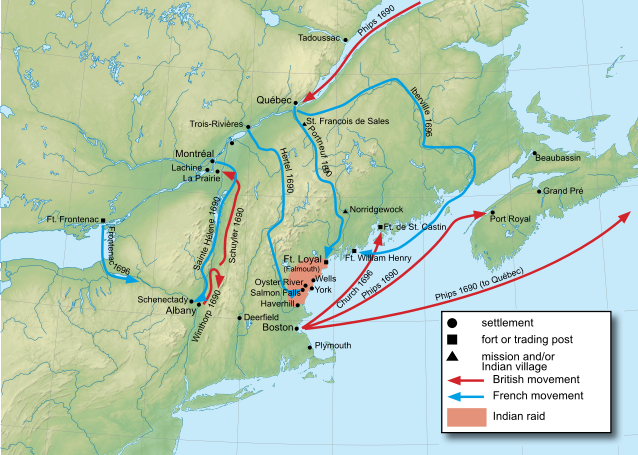

The early years of the province were dominated by the Salem witch trials and by King William’s War (1689–97). In the aftermath of the revolt against Andros, colonial defenses had been withdrawn from the frontiers, which then repeatedly were raided by French and Indian forces from Canada and Acadia. War again broke out in 1702 with Queen Anne’s War, which lasted until 1713. Massachusetts Governor Joseph Dudley organized the colonial defenses, and there were fewer raids than in the earlier war. Dudley also organized expeditions against Acadia, a haven for French privateers, in 1704 and 1707, and requested support from London for more ambitious efforts against New France. In 1709 Massachusetts raised troops for an expedition against Canada that was called off, and again in 1710, when Port Royal, the Acadian capital, was finally captured.

Because of the wars, the colony had issued paper currency, whose value was constantly in decline, leading to financial crises. This led to proposals to create a bank that would issue notes backed by real estate, but this move was opposed by Governor Dudley and his successor, Samuel Shute. Dudley and Shute, as well as later governors, engaged in fruitless attempts to convince the general court to fix salaries for crown-appointed officials. The issues of currency and salary were both long-lived issues over which governors and colonists fought. The conflict over salary reached a peak of sorts during the short-lived administration of William Burnet. He held the provincial assembly in session for six months, relocating it twice, in an unsuccessful attempt to force the issue.

In the early 1720s the Abenaki of northern New England, encouraged by French intriguers but also concerned over British encroachment on their lands, resumed raiding of frontier communities. This violence was eventually put down by Acting Governor William Dummer, leading the conflict to be called Dummer’s War (among many other names). Many Abenakis retreated from northern New England into Canada after the conflict.

In the 1730s Governor Jonathan Belcher, a native son, disputed the power of the legislature to direct appropriations, vetoing bills that did not give him the freedom to disburse funds as he saw fit. This meant that the provincial treasury was often empty. Belcher was, however, permitted by the Board of Trade to accept annual grants from the legislature in lieu of a fixed salary. Under his administration the currency crisis flared again. This resulted in a revival of the land bank proposal, which Belcher opposed. His political opponents intrigued in London to have him removed, and the bank was established. Its existence was short-lived, for an act of Parliament forcibly dissolved it. This turned a number of important colonists (including the father of American Revolutionary War political leader Samuel Adams) against crown and Parliament.

The next twenty years were dominated by war. King George’s War broke out in 1741, and Governor William Shirley rallied troops from around New England for an assault on the French fortress at Louisbourg. which succeeded in 1745. However, much to the annoyance of New Englanders, Louisbourg was returned to France at the end of the war in 1748. Governor Shirley was relatively popular, in part because he managed to avoid or finesse the more contentious issues his predecessors had raised. He was again militarily active when the French and Indian War broke out in 1754. Raised to the highest colonial military command by the death of General Edward Braddock in 1755, he was unable to manage the large-scale logistics the war demanded, and was recalled in 1757. His successor, Thomas Pownall, oversaw the colonial contribution to the remainder of the war, which ended in North America in 1760.

The 1760s and early 1770s were marked by a rising tide of colonial frustration with London’s colonial policies, and with the governors sent to implement and enforce them. Both Francis Bernard and Thomas Hutchinson, the last two non-military governors, were widely disliked over issues large and small, notably the Parliament’s attempts to impose taxes on the colonies without representation. Hutchinson, a Massachusetts native who served for many years as lieutenant governor, authorized the quartering of British Army troops in Boston, which eventually precipitated the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. By this time, agitators like Samuel Adams, Paul Revere, and John Hancock were active in opposition to crown policies. After the Boston Tea Party in December 1773, Hutchinson was replaced in May 1774 by General Thomas Gage. Gage was at first well-received, but the reception rapidly became worse as he began to implement the so-called Intolerable Acts, including the Massachusetts Government Act, which dissolved the legislature, and the Boston Port Act, which closed the port of Boston until reparations were paid for the dumped tea. The port closure did great damage to the provincial economy, and led to a wave of sympathetic assistance from other colonies.

The royal government of the Province of Massachusetts Bay existed de facto until early October 1774, when members of the General Court of Massachusetts met in contravention of the Massachusetts Government Act and established the Massachusetts Provincial Congress. Although Governor Gage continued an essentially military rule in Boston, the provincial congress had effective rule in the rest of the province. Hostilities starting the American Revolutionary War broke out in April 1775 at Lexington and Concord, which continued with the Siege of Boston. The British evacuated Boston on March 17, 1776, ending the siege and bringing the city under rebel control. On May 1, 1776 the provincial congress adopted a resolution declaring the province to be independent of the crown; this was followed up by the United States Declaration of Independence on July 4, 1776 declaring the independence of all of the Thirteen Colonies.

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts was agreed upon in Cambridge in October 1779 and adopted by the delegates nine months later in June 1780, to go into effect “the last Wednesday of October next”. In elections held in October 1780, John Hancock was elected the first Governor of Massachusetts along with representatives to the commonwealth’s first General Court.

Politics

Provincial politics

According to Thomas Hutchinson, who wrote the first major history of colonial Massachusetts, the politics of the province was dominated by three major factions. This is in distinction to most of the other colonies, where there were two factions. Expansionists, exemplified in Massachusetts by people like Thomas Hancock, uncle to John Hancock, and James Otis, Sr., believed strongly in the growth of the colony and a vigorous defense against French and Indian incursions. This faction became a vital force in the Patriot movements preceding the revolution. Nonexpansionists, exemplified by Hutchinson and the Oliver family of Boston, were more circumspect, preferring to rely on a strong relationship with the mother country. This faction would become Loyalist in the revolutionary era. The third force in Massachusetts politics was a populist faction made possible by the structure of the provincial legislature, in which rural and lower class communities held a larger number of votes than in other provinces. Its early leaders included the Cookes (Elisha senior and junior) of Maine, while later leaders included revolutionary firebrand Samuel Adams. Although religion did not play a major role in these divisions, nonexpansionists tended to be Anglican, while expansionists were mainly middle-of-the road Congregationalist. Populists generally held either conservative Puritan views or the revivalist views of the First Great Awakening. Throughout the provincial history, these factions made and broke alliances as conditions and circumstances dictated.

The populist faction had concerns that sometimes prompted it to support one of the other parties. Its rural character meant that when there were troubles on the frontier, they sided with the expansionists. They also tended to side with the expansionists on the recurring problems with the local money, whose inflation tended to favor their ability to repay debts in depreciated currency. These ties became stronger in the 1760s as the conflict with Parliament grew.

The nonexpansionists were composed principally of a wealthy merchant class in Boston. They had allies in the wealthy farming communities in the more developed eastern portions of the province, and in the province’s major ports. This alliance often rivalled the populist party in power in the provincial legislature. It favored stronger regulation from the mother country, and opposed the inflationist issuance of colonial currency.

Expansionists mainly came from two disparate groups. The first was a portion of the eastern merchant class, represented by the Hancocks and Otises, who harbored views of the growth of the colony and held relatively liberal religious views. They were joined by wealthy landowners in the Connecticut River valley, whose needs for defense and growth were directly tied to property development. Although these two groups agreed on defense and an expansionist vision, they disagreed on the currency issue, with the westerners siding with the nonexpansionists in their desire for a standards-based currency.

Local politics

The province significantly expanded its geographic reach, principally in the 18th century. In 1695 there were 83 towns, which grew to 186 in 1765. Most of the towns in 1695 were within one days’ travel of Boston, but this changed as townships sprang up in Worcester County and the Berkshires on land that had been under Indian control prior to King Philip’s War.

The character of local politics changed as the province prospered and grew. Unity of community during the earlier colonial period gave way to subdivision of larger towns. Dedham, for example, was split into six towns, and Newburyport was separated from Newbury in 1764.

Town meetings also became more important in local political life. As towns grew, the townspeople became more assertive in managing their affairs, and the town selectmen, who had previously wielded significant power, lost some of their influence to the town meetings and to the appointment of paid town employees, such as tax assessors, constables, and treasurers.

Geography

The boundaries of the province changed in both major and minor ways during its existence. Nova Scotia, then including New Brunswick, was occupied by English forces at the time of the charter’s issuance, but was separated in 1697 when the territory, called Acadia by the French, was formally returned to France by the 1697 Treaty of Ryswick. Nova Scotia became a separate province in 1710, following the British conquest of Acadia in Queen Anne’s War. Maine was not separated until after American independence, when it attained statehood in 1820.

The borders of the province with the neighboring provinces underwent some adjustment. Its principal predecessor colonies, Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth, had established boundaries with New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, but these underwent changes during the provincial period. The boundary with New Hampshire was of some controversy, since the original boundary definition in colonial charters (three miles north of the Merrimack River) had been made on the assumption that the river flowed predominantly west. This issue was resolved by King George II in 1741, when he ruled that the border between the two provinces follows what is now the border between the two states.

Surveys in the 1690s suggested that the original boundary line with Connecticut and Rhode Island had been incorrectly surveyed. In the early 18th century joint surveys determined that the line was south of where it should be. In 1713 Massachusetts set aside a plot of land (called the “Equivalent lands”) to compensate Connecticut for this error. These lands were auctioned off, and the proceeds were used by Connecticut to fund Yale College. The boundary with Rhode Island was also found to require adjustment, and in 1746 territories on the eastern shore of Narragansett Bay (present-day Barrington, Bristol, Tiverton and Little Compton) were ceded to Rhode Island. The borders between Massachusetts and its southern neighbors were not fixed into their modern form until the 19th century, requiring significant legal action in the case of the Rhode Island borders. The western border with New York was agreed in 1773, but not surveyed until 1788.

The province of Massachusetts Bay also laid a claim to what is now Western New York as part of the province’s sea-to-sea grant. The 1780s Treaty of Hartford saw Massachusetts relinquish that claim in exchange for the right to sell it off to developers.